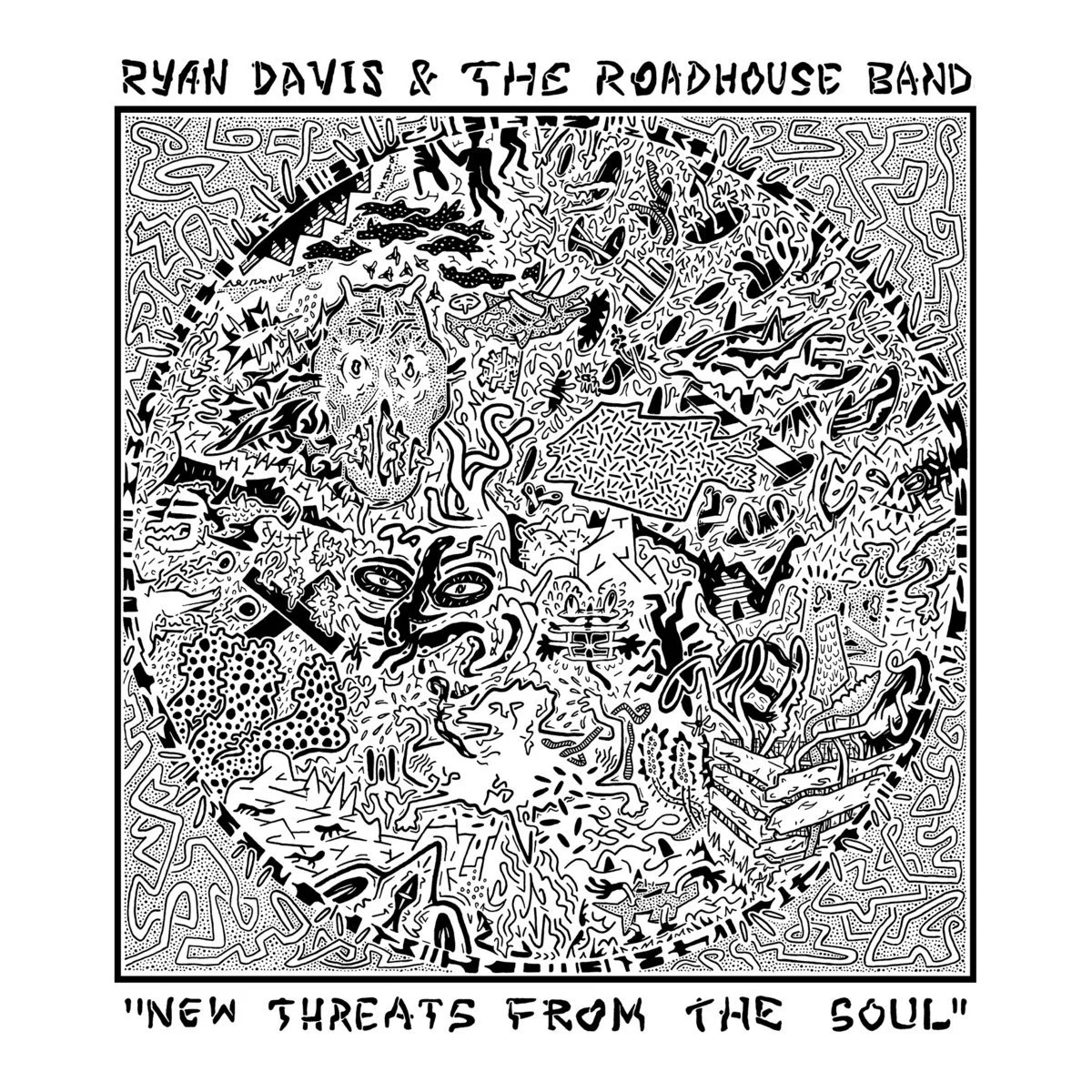

by Rohan Press (@burnsoutatmidnight)

Obsessed with a book I wasn’t nearly old enough to understand, I first visited Walden Pond when I was 16, my first time east of the Mississippi. I’d never have guessed, back then, that a decade later, I’d be living only a few miles away from Thoreau’s pond and be working for the same agency that manages it—the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation. All its historical glamor notwithstanding, it’s been a frustrating job, and so it hits hard when singer-songwriter Ryan Davis slyly reinterprets this birthplace of American ecological idealism as a pawnshop—“Walden Pawn.” A place where dreams are ditched; a place where (as he says on the title track) he’s just “a caged bird swingin’ from a chain swing, […] whistling for my pay seed.” Shit. Davis doesn’t shy away from it: “The more that’s within you, the more that gets sold.” The deeper the idealism and the romanticism (a sensibility, I suspect, that he and I and Thoreau share), the more painful it’s gonna be—the more you’re gonna have to give up. In this vein, I think it’s important that his profound, profane, and probing new album is called New Threats from the Soul, not New Threats for the Soul—its line of questioning has less to do with external obstacles to spiritual and emotional fulfillment, and more with our ineluctable and hardwired self-inhibitions.

So here he is, on this peripatetic, post-country pilgrimage: a romantic caught by his own dreams—“these cruel transferences from the mirror world.” Shoulders stooped by romantic loss, spiritual loss, material loss, in a world that was supposed to mean and be so much more. Across these long, impressionistic songs, Davis drifts from one studied and devastating observation to another, like a prophet suspicious of his own prophecy; and his songs’ longform structures, segueing from bridge to bridge and only sparingly returning to familiar melodic anchors, mirror his existential disorientation.

New Threats from the Soul isn’t just a collection of voluble country rock songs; it’s an entire psychic and existential landscape, a place to rest and to rove in the heart of these questions. The contours of this interior geography are defined by “Mutilation Springs” and “Mutilation Falls,” two songs which repurpose the same lyrical and melodic motifs in a subtle, powerful, emotional cross-pollination. Listening to the two of them, anchoring the middle of A-side and the B-side, respectively, is like hiking along a creek you keep on fording, back and forth: it’s the same, swirling stream brushing your shins, but it isn’t the same water. And by the time all that mutilation drops off at its eponymous waterfall, something’s different—all that desperate disillusionment, all that damning love for “little miss mutilation,” has opened up to something. “Lightning found me here,” Davis exhales. “You found me here. At Mutilation Falls. In Mutilation Springs.”

Yes, our past selves and loves are irrecoverable; our dreams are nothing more than “a mirror held by a phantom hand”—but keep listening; hidden in the timid echo of those backing vocals (supplied by Catherine Irwin of Freakwater), there’s more: “Hope, it’s said, comes from within though,” she whispers, barely audible, all alone and without Davis’ assurance.

And so, stranded between dreams and hopes, the soul may well torment us, and may well be the source of “threats on top of threats from within.” But it’s also there, from within, that there’s some hesitant hope, even if it’s a hope that’s bruised again and again. “Seems the dream is dead, but the hopes are necrophiliac.” A dead dream is painful, and Davis knows it, but maybe there’s something to what it means to feel it die; maybe all that pain is the soil from which something else could one day spring. This isn’t some triumphant resurrection of hope and love over loss and loneliness; it’s an acknowledgement that life’s deepest components are twofold: “simple joy, simpler loneliness.” You can’t have the one without the other, and both are found within that same goddamn soul.

That’s the most remarkable thing about New Threats: it’ll damn you and it’ll reveal you; it’ll catch you sniffing for the transcendent down in the muck and the weeds. For me, it’s all there in that tangled symbolism of “Crass Shadows (at Walden Pawn),” the closing track. Because maybe Walden Pawn represents more than just the cynical backslide of idealism into realism: maybe it’s also, like “Mutilation Falls,” a place to pawn off all those things you just won’t let go of, to leave yourself simple and bare and open. “When what’s left in my wallet’s gone,” Davis assures us, “I’ll be down at Walden Pawn / Waiting on my assignment from the spirit world.” The album ends there, with this evocation of spiritual possibility in the heart of its apparent cynical relapse. And so, this pawnshop where we all seem to end up is both a place to feel the pain of loss, and a place to hold out against it—to sell your possessions when you’re down on your luck, but also to do so as a spiritual and romantic gesture, like Thoreau’s very gesture. Maybe Walden Pawn is the perfect, painful place for lightning to strike after all—for some memory of that promised, absent love to find you, and to say to you, as Ryan Davis says to us: “Tie a ribbon to the bus stop; I’ll be back when the well is dry.”