by Christopher J. Lee (@joonhai)

By definition, archival recordings comprise a somewhat academic genre for listeners. Whether bootlegs, demos, B-sides, or other such ephemera, they are not what a band or musician chose to release or foreground in the first instance. Hence, the primary audiences for such material are largely diehard fans – committed students, essentially – as opposed to new or recent converts. Taken further, the release of archival recordings is often understood as a minor cash grab, a means of capitalizing on leftovers while musicians or band members are still alive and copyright matters are clear. The emergence of new platforms and the continued popularity of past formats (vinyl) have only heightened attention to this commercial opportunity.

However, while this market aspect is true in many instances, it is perhaps more interesting to think about the release of archival recordings as a self-conscious act of disruption and messing with the legacies of the band at hand – a moment of unsettlement, even self-immolation, rather than artistic affirmation. In this regard, archives, whether of sound recordings or other material, are not only repositories of memory, but also places of friction and conflict. Shining a light on neglected cul-de-sacs and past desire, they can project competing, even opposing, interests and expectations.

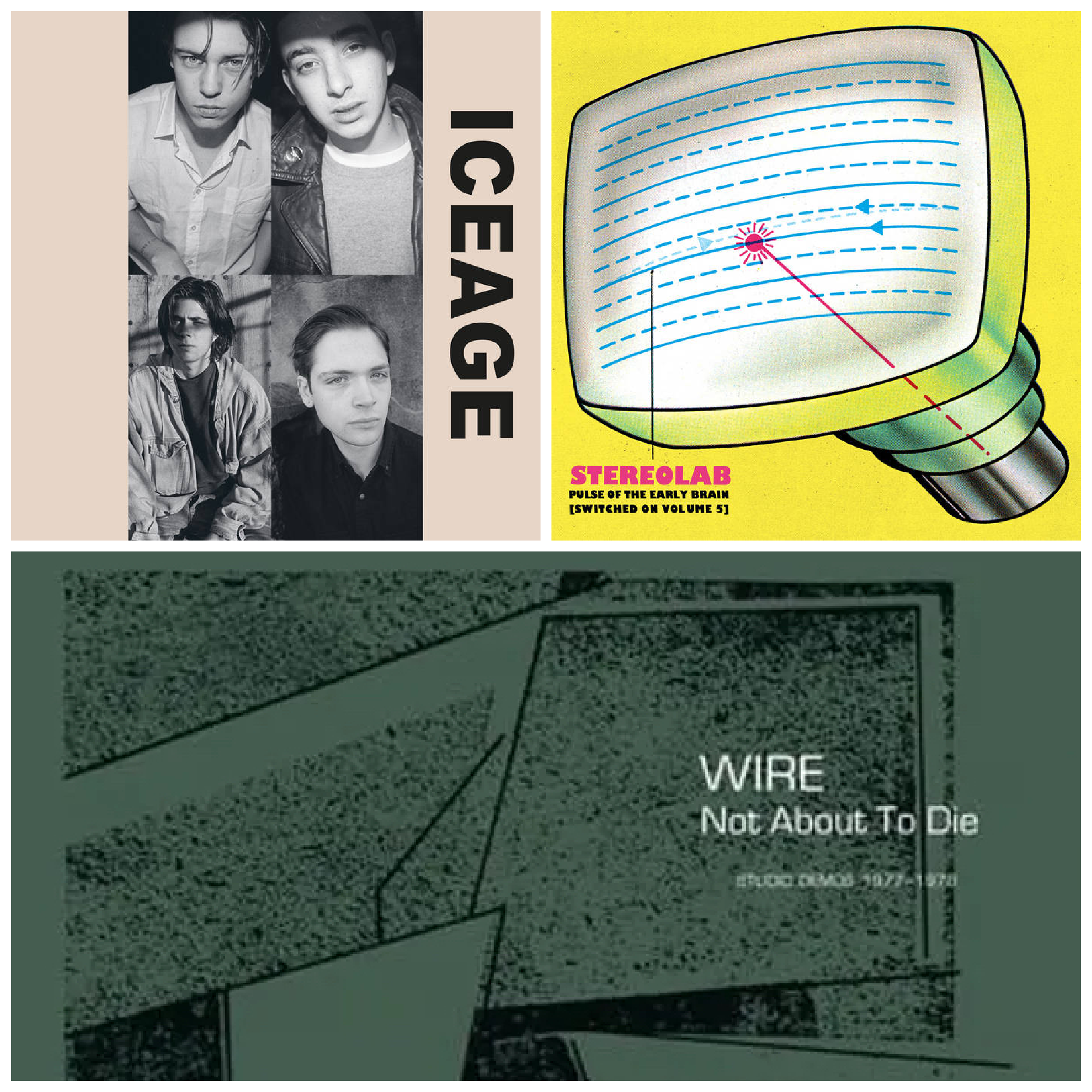

These latter thoughts apply to the albums under review by Wire, Stereolab, and Iceage, though they are not alone. The past eighteen months have seen an abundance of archival recordings being released (Prince, Blondie, Rush, etc.), among the most prominent being Bob Dylan’s The Bootleg Series Vol. 17: Fragments – Time Out of Mind Sessions (1996-1997), which is part of a long-standing regular series and is a mouthful to say and to write down. It is also a paradigm of the positions just mapped out. Is this for die-hard aficionados? Check. Is it a cash grab? Check. Does it complicate Dylan’s legacy a bit? Also check. In contrast, the albums Not About to Die (Studio Demos 1977-1978) (Wire), Pulse of the Early Brain (Switched On Volume 5) (Stereolab), and Shake the Feeling: Outtakes & Rarities, 2015-2021 (Iceage) achieve these aims in more uneven, though also more interesting, ways.

Not About to Die (Studio Demos 1977-1978) (Pink Flag) is a compilation of demos that concentrate on the two-year period when the then-members of Wire – Colin Newman (vocals, guitar), Graham Lewis (bass), Bruce Gilbert (guitar), and Robert Grey (a.k.a. Robert Gotobed, drums) – were writing and recording their second and third albums, Chairs Missing (1978) and 154 (1979), respectively. This focus consequently provides a documentary glimpse of a band still teetering on that precarious path between making a highly impactful debut and progressing forward in a way that is consistent but not repetitious. Indeed, their first album Pink Flag (1977) remains canonical, whose shadow the band has never entirely escaped. The title of this new archival release underscores a set of anxieties regarding initial success and the need to prove it wasn’t all a fluke. Somewhat ironically, Wire did, in fact, go on hiatus after 154 for about seven years until the release of their fascinating Snakedrill EP (1986), which began to introduce an electronic/industrial sound to their existing guitar-based repertoire. This period of absence explains the circulation of Not About to Die during the early 1980s as a treasured bootleg.

Wire have always understood an essential element of songcraft and its potential for popularity, which is to keep things short, simple, and open to interpretation. The timing of their start has located their music to the era of punk/post-punk, but their minimalist ethos is also deeply aligned with the basic essence of rock ‘n roll, which partly explains their longevity. Consisting of eighteen tracks at just under forty minutes, Not About to Die offers few surprises from a musical standpoint – that impeccable Wire sound endures – even when there are stark differences. For example, the track “French Film (Blurred) [4th Demo]” is half as long as the released version on Chairs Missing, being just over a minute and possessing a faster, frenetic pacing akin to classic tracks on Pink Flag. In contrast, the final version of “French Film Blurred” has a slower, moodier tone, parts of which may remind listeners of much later Pavement compositions like the second half of “Fight This Generation” from Wowee Zowee (1995). The beguilement with this officially released bootleg, then, regards these revisions, which indicate a band in motion and a creative process of at times dramatic rethinking, even if the actual discussions and decisions for such reconsiderations remain unexplained and enigmatic.

Pulse of the Early Brain (Switched On Volume 5) (Warp Records) is an entirely different listening experience in terms of scale, chronology, and type. Consisting of twenty-one tracks and lasting nearly two hours (118:54 minutes), this is an album, like Not About to Die, designed for pre-existing fans. In contrast to Not About to Die, however, which coalesces around a particular period and, as a consequence, possesses a particular sound, Pulse of the Early Brain roams across Stereolab’s career with effects that range widely. Chronologically, the songs included draw from the early 1990s – Stereolab started in 1990 and has been co-led by Laetitia Sadier and Tim Gane – up to the late 2000s. In this respect, the thematic cohesion of this LP is less clear. Indeed, Stereolab have been releasing compilation albums of this kind since 1992 when the first album with the Switched On moniker was put out. They have been unfailingly studious and committed to this self-reflective archival genre. Yet this new LP has the feel of decluttering. It is not framed around a tight period or cohesive style, imparting a contradictory unwieldiness that relies on the strength of individual tracks rather than a general sense of album-ness.

Nonetheless, a number of these compositions are fascinating, due to their evincing and tracing of Stereolab’s long and restless evolution. The two opening tracks provide a good example. The first, “Simple Headphone Mind,” is a collaboration with the cult experimental project Nurse with Wound dating from 1997. It clocks in around ten minutes, providing trial tests with modified vocals and birdsong over a trance/danceable synth beat. Not to be outdone, the second track, “Trippin’ With the Birds,” also with Nurse with Wound from 1997, is an extended sequel that doubles the length at twenty minutes. These two songs originally appeared on a limited-edition vinyl twelve-inch. Taken together, they pay homage to krautrock and Kraftwerk/Neu! specifically, displaying the ambient/drone origins of Stereolab’s neo-psychedelic sound. Releasing these rarities in a more widely available format is cause for excitement.

The remainder of the album wanders hither and thither from this starting point. The third track “Low Fi” (from the 1992 Low Fi EP) has a clear “Sister Ray”/Velvet Underground vibe, while the previously unreleased “Robot Riot” has the updated Feelies’ rhythmic guitar sound that defined Stereolab during the mid-1990s circa Mars Audiac Quintet (1994). In contrast, the instrumental “Symbolic Logic of Now!,” one side of a split 7” from 1998, provides a jazzy interlude. Meanwhile, the garage-rock “ABC” from 1996 is a cryptic cover of a tune by the ‘60s improv noise band The Godz. “Magne-Music,” which is a softer, danceable synth-pop composition, is a bonus track from Stereolab’s later LP Chemical Chords (2008).

Some tracks like “Yes Sir! I Can Moogie” are not songs per se but just ideas. Barely over a minute long, this one dates from 1995, and it has a rhythmic clip and organ melody that also echoes the sound on Mars Audiac Quintet. “Refractions In The Plastic Pulse (Feebate Mix) – Autechre Remix” (dating from 1998) is genuinely odd, which I risk saying is unlike anything found in their catalog, though its curious looping techniques prefigure approaches later found on Radiohead’s Kid A (2000), especially compositions like “Idioteque.”

You get the idea. The album closes with “Cybele’s Reverie (Live at the Hollywood Bowl),” which, as the name suggests, is a live track from 2004. Originally recorded for Emperor Tomato Ketchup (1996), which itself is named after a 1970 experimental film by Japanese poet-director Shūji Terayama (1935-83), it is the only such track on the LP making it a strange inclusion, though perhaps no stranger than anything else. As the closer, it lets some air in, revealing a sense of Stereolab as a live band, which is significant – despite studio experiments, they can be amazing live. Overall, Pulse of the Early Brain is a shaggy, baggy release that zigzags across Stereolab’s history with prized rarities and minor oddities that capture the competing musical impulses that shaped the band during its prime. Similar to Wire, Stereolab also went on hiatus, which demarcates the endpoint of Pulse of the Early Brain circa 2008/2009. Yet, in many ways, their release is the antithesis of Not About to Die.

Shake the Feeling: Outtakes & Rarities 2015-2021 (Mexican Summer) from Iceage is the least complicated of the three releases under review. That sounds like a knockdown, but in certain ways it is a strength. Unlike the snapshot historical document that is Not About to Die and the sprawling Pulse of the Early Brain, which in artistic spirit resembles something like Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights, this LP doesn’t have the weight or hindsight needed to attach an essential importance to it. Instead, with twelve tracks at roughly 45 minutes, it’s a cool, fun listen that is readily accessible to new fans.

Founded in 2008 and based in Copenhagen, Iceage have released five full-length LPs beginning with New Brigade (2011) and landing most recently with Seek Shelter (2021). Each album has been critically acclaimed, with their music assembling elements of punk, post-punk, garage rock, soul, and blues into a frequently aggressive, vintage sound. Equally important, their lead singer and main songwriter, Elias Bender Rønnenfelt, has a distinctive crooning vocal style that resembles Nick Cave, Hamilton Leithauser of the Walkmen, or Steve Kilbey of the Church, depending on the song. Let me also throw in You Ishihara from the Tokyo psych-rock outfit White Heaven for good measure. In short, Rønnenfelt’s emotive singing and its charismatic moods have largely defined the tone for Iceage across their albums, habitually imparting a brooding, despairing, or mournful quality to the proceedings.

Shake the Feeling covers the fertile period just after their third album, Plowing into the Field of Love (2014), up through Beyondless (2018) and Seek Shelter. During this time, they experimented with their sound through the addition of horns, strings, and guest vocalists (Sky Ferreira), which added more layers to their work. The excellent Seek Shelter had the involvement of Sonic Boom as a producer and whose post-Spaceman 3 oeuvre has ranged widely, which may explain the guitar-centric-ness on some of the tracks (“Shelter Song”) combined with, say, a Rolling Stones boogie as heard on “Vendetta.” The album maintains enough variety to keep things surprising. There are musical parallels to be drawn with British acts like Arctic Monkeys and the Libertines.

In contrast, Shake the Feeling pulls back, stripping things down, which is unsurprising for a set of demos and outtakes. The first track, “All the Junk on the Outskirts,” is a stylish, nervously paced road song, setting the tone with its dissolute, jittery tempo. The second, bar band sounding title track “Shake the Feeling” has a chaotic guitar disorder and percussion clatter that recalls Uncle Tupelo or Buffalo Tom, while its successor, “Sociopath Boogie,” evokes the early White Stripes and the Replacements before they went major label. There are two covers, which are obligatory for an LP of this kind – one by Dylan and the other by the Black folk musician Abner Jay. The rendition of Dylan’s “I’ll Keep It with Mine” is deeply felt, if a bit foreseeable like many covers of Dylan. The inclusion of Jay’s “My Mule” is more revelatory in terms of citation, albeit an eccentric, harder listen in the spirit of Jay. The album closes with a sequence of three tracks – “Order Meets Demand,” “Lockdown Blues,” and “Shelter Song (Acoustic)” – which say different things about this band’s influences, its range, and its possible futures. The first is stellar, distantly recalling the Stones circa Aftermath (1966) as filtered through the lo-fi instincts of early ‘90s Pavement and Silkworm. The second is a well-intended Covid-era track, as the title suggests, though it probably won’t endure. The third and last, which allows Rønnenfelt’s soulful vocals to shine, teases the idea of more acoustic work on the horizon from a band that is accustomed to rocking out.

Taken together, these recent releases listened to in chronological order offer a panoramic view of singular, but related, parts and shifts in the music scene, closing in on five decades. It is important to mention that these three bands are still active. In different ways, they have been attendant to their legacies. As noted, Stereolab has long been diligent toward assembling their ephemera. Wire has similarly released a remarkable series of over two dozen live recordings, many originally bootlegs, in addition to numerous compilations. Though the youngest, Iceage has progressed far enough such that archival considerations will become more prominent.

While there is a nominal profit motive involved with these new releases – musicians have to sustain themselves after all – this aspect is arguably less relevant, if only because the material is less commercial to begin with. Repackaged archival recordings aren’t always an extension of capital repurposing material. The intrinsic value of these releases isn’t with their market potential but principally rests with their artistic example. These are bands making music on their own terms. Holding a mirror to time, these recent archival LPs present hidden transcripts and forgotten ideas, serving as mislaid Rosetta stones for sorting through the past and divining lost futures, some of which may still be fulfilled.