by Khagan Aslanov (@virgilcrude)

As I sit down to talk with Martin Kanja, the avant-metal spitfire, better known by his stage handle Lord Spikeheart, I can hear the walls around me hum and vibrate. The road crew outside is ripping up the sidewalks of the neighbourhood. This sets an appropriately noisy backdrop for my interview with one of the most clamorous and chaotic figures in contemporary metal, experimental music, breakcore and far beyond.

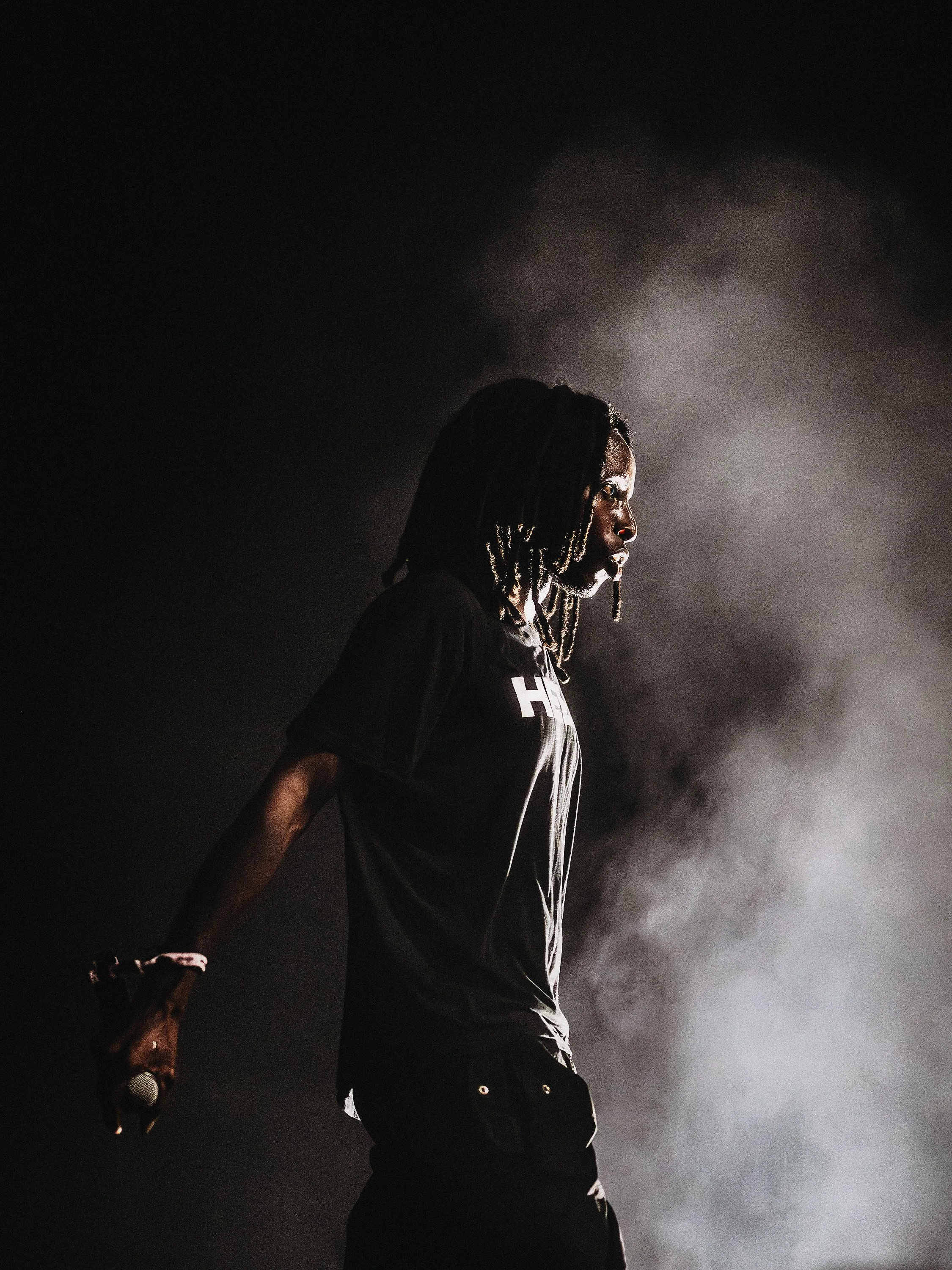

Lord Spikeheart by Fernando Schlaepfer

For those keeping a close ear to the underground metal club scene, the name Lord Spikeheart would have first clocked around 2019, as one half of the avant-garde act Duma, whose hot-headed and omnivorous music schisms broke them through in quick succession – first out of their home-base in Nairobi, then out of East Africa and into Europe, and soon after, on the heels of their Nyege Nyege Tapes debut album, into just about every record shop, DJ club, and underground venue around the world. Then, just as suddenly as they sprung to life, in 2023, Duma was no more.

Yet Lord Spikeheart spent little time resting on his newly formed laurels. Just a year after Duma’s dissolving, he dropped The Adept, a record steeped in frenzied vocal progressions, cavernous beats and metal indignation. It was evident from the first notes of The Adept that his voracious, havoc-prone approach to music-making had only amplified. Spikeheart still relishes in creating sounds that travel on the most contorted vectors. The Adept promptly crashed its way to the top of many critics’ polls that year, solidifying both Lord Spikeheart’s solo path, as well as helping him forge Haekalu Records, his own imprint.

For Kanja, a career in music, even growing up in the relative remoteness of Nakuru, Kenya, was somewhat of an ordained path:

“I began performing at seven. There was music in the household. My brother and sister used to be musicians. My uncle was in touring bands in the 80’s. I always knew I wanted to pursue music, I just didn’t know what kind. Then, after I left high school, I started listening to metal and rock. And soon after, one Sunday, I formed my first band.”

The band in question, Lust of a Dying Breed, established Kanja’s tack early on. Though the overall tone of these early songs plies close to the traditional modalities of metal and grindcore, his vocalizations were already something to behold. With a dense echoing growl or an anarchic, desperate screech, he was already exploring alternate spectrums, inducing bedlam and unease. Learning how to scream like that without straining came with time and practice:

“I couldn’t afford instruments. All I had was my voice. But I used to blow my voice every night. If the show was on Saturday, I would start talking again on Tuesday. I wasn’t using my diaphragm, just my vocal chords, and pushing it too far. But screaming is exactly like singing, so I had to learn normal singing first. I learned how to hold my abdomen, hold notes, add falsetto techniques. I would practice in the maize farm. Every night at 11:00, I would go into the maize farm, and pretend the corn were people at a show. And after a very long time, I learned how to do it.”

Though Kanja’s trajectory did finally lead him out of obscurity, it also serves to demonstrate all that has been lost to the global listening public over generations. African fringe art, specifically East African guitar and electronic-driven music, has been around for a long, long time, but it’s only recently that the world has finally caught on to the multitude of local bands that have spent decades probing and picking away at the established boundaries of sound. Some of it, invariably, has to do with systemic isolation, disinterest and the ensuing post-colonial fetishism. But at this moment in time, it is Lord Spikeheart who stands at the sword’s tip. His fearless advances have thrust Kenya and East Africa into the focus of the listening public:

“I was sixteen years old. There was a huge community of us in Nairobi! And we had friends in Botswana, in South Africa, Egypt, Angola, Mozambique, Nigeria, all doing metal. We all met each other, became friends on the scene. There were university kids, living in hostels, coming to see shows, forming bands, sharing instruments. There was also a businessman on the scene who loved rock. He owned a bar on Baricho Road, in Mombasa, called Choices. And he gave it to the scene. It was a safe space, where we could be outside until late. We held shows there almost every night. A lot of great bands formed in that club.”

Like most metal-heads, when not directly engaging with the genre’s perception as a dark and kinky subculture, on the domestic front, Kanja projects as the most genial person in the world – he speaks eagerly and openly, laughs with great uproar and pleasure, seems wholly consumed with love of exploring sound, and quickly steers our interview out of formality, and into something closer to an affable chat.

All of this is mirrored in his art itself, of course. For all the surface-level aggression that courses through in his songs, at its very core, this is music laden in love and life, something that embodies empowerment of self, rather than empty-souled thrashings.

Though there is another level to all this, as these things usually go. The Adept is dedicated to Kanja’s great-grandmother, Muthoni wa Karima, a legendary Field Marshall, who took on a pivotal leadership role in the Mau Mau Uprising against British colonial rule in Kenya. She was the only woman to achieve the rank, and spent more than a decade waging guerilla warfare against the British, living in near-starvation and fighting powers that were better armed and trained.

Though ultimately defeated on the militaristic front, the uprising became a catalyst to Kenya’s establishment as a republic. Since then, like most countries that manage to climb out from under the colonial thumb, it has been trying to stabilize itself against several regimes and unrests – the Kenyatta Senior era, forging a democratic multi-party system, the fall of the National Front, violence and opposition, the Kenyatta Junior era - all while the whiplash and holdovers of colonialism still linger in the region.

In light of all this, and his great-grandmother’s legacy, it seemed self-evident to ask Lord Spikeheart if the music he makes is something he views as protest art, or if it even has a choice to be anything else:

Khagan Aslanov: Do you think you make protest music?

Lord Spikeheart: I don’t think so. Not really. Maybe some other term is better. My music speaks about empowerment. About self-actualization. These are things I’ve been exposed to, things I’ve lived. To a degree, there may be some protest there. But by the same measure, there is also spirituality, land reclamation, natural resources, colonialism, economics, resilience. It’s a wide range of what makes a people. It’s all about coming back to yourself. Something solution-based.

KA: You may be right. I mean, I might assume aggressive music projects aggression. But when I listen to your music, I feel good.

LS: Yes! That’s the point! That’s the entire idea. It starts as fringe, some people making something strange. But eventually, it all becomes pop.

As it all stands now, Lord Spikeheart is in a damn good place. He has a new EP out, one that continues his lifelong affair with loud and dissonant art. He’s looking to branch out his vocals into other genres, like free jazz, chanting, and spoken word. He continues touring Europe, eyeing Trumpian North America warily as his next stomping ground. And he’s got ambitious plans to grow Haekalu Records into a resources platform for future generations of outsider music, and everything it might become.