by Khagan Aslanov (@virgilcrude)

*Author’s Note – this interview was conducted in Autumn, 2024

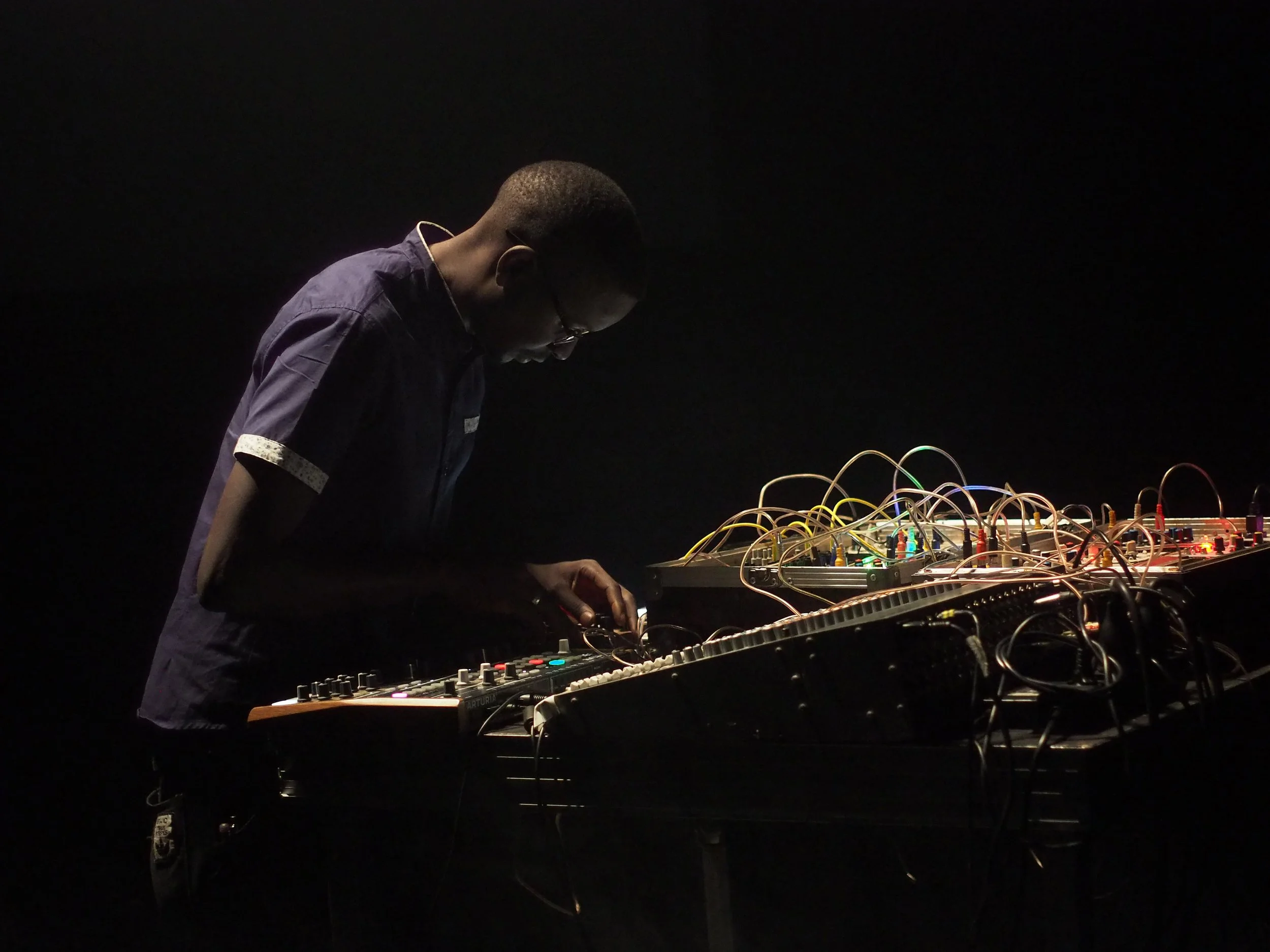

I formally meet Brian Bamanya, better known by his stage name Afrorack, in the back parking lot of a small nightclub the morning after watching his show. He’s packing up equipment, carefully dismantling custom-built percussion modulators, storing away sine wave oscillators and circuit boards, and untangling a gargantuan knot of wires into milk crates and loading them into the trunk of a car. While doing all of this, he’s having a video conversation with his young daughter, tenderly scolding her for playing with the hand-crafted instruments inundating their home.

Bamanya was born and raised in Kabale, a small town close to Uganda’s Rwandan border. It was a cut-off place without many outlets into the information and plenitude of the outside world. The only access available on television without extra pay was the nationalist propaganda channel. Still, there were some tech appliances at his disposal, courtesy of his father’s job. The son of a civil servant under Idi Amin’s reign, their house was filled with modern gadgetry that was gifted as passive kickbacks to keep governmental workers placated.

Afrorack by Udo Siegfriedt.

“As a kid, I would always pull things apart. I would open up motorized toys and my father’s gadgets. I wanted to see what was inside. To me, it was more interesting to see the motor and connectivity within than the device itself.”

Once he opened the family’s tube television and narrowly avoided a massive electrical shock that could have killed him. But the incident did little to curb his curiosity and flowering obsession with how recursive electronic signals worked.

His father’s job also allowed him access to a British-style school with a library and computers. It was there that he began reading about transistors and examining blueprints of mechanical and electric engines. Naturally, he thrived in Physics, and though that early interest was probably expected to lend itself to joint success in Mathematics and a future in engineering, Bamanya is quick to point out that the less hands-on, a priori approach of Maths never clicked with him:

“We had this Mathematics teacher that we never liked. He would always present us these complicated problems that we couldn’t solve. We began calling him Problems. I lost interest in his class, and instead would sit in the library, reading about engines. So I never got into Engineering. The compromise was Computer Science.”

There again, Bamanya’s interest in internal mechanisms was both an obstacle and a catalyst toward a new horizon. Though he learned to program, the practical, career-seeking lean of the education did not align with his curiosity. But it was then that his attention turned to music for the first time:

“In 2000, the top hits were all rock music. I picked up an electric guitar. But when I plugged it in and played, it didn’t sound like them. And so I started trying to build my own guitar effects. Sometimes it worked, other times, not. I couldn’t explain why.”

Though his fascination with guitar ebbed quickly, how effects altered its output stayed. So began Bamanya’s path to understanding how sound can be bent, distorted, and programmed to travel on odd trajectories.

“I read about Moog. I saw pictures of these futuristic devices with many cables. I watched videos and read about it. It looked interesting, but I couldn’t afford it. So I watched videos of how Moog built their stuff. Obviously, for (Ugandans), going to Ebay to buy parts wasn’t an option. So I scavenged through thrown-away electronics, separated and re-used parts.”

The first things he built were simple drum machines, in the fashion of Roland 808’s, controlled analog signals that couldn’t be changed after they were triggered.

“At the time, companies published service manuals because they expected you to fix something if it broke. From there, I was able to see and learn all this stuff, like how a snare sound is generated, for example. I started seeing the potential of how to build things. From all this excitement, I built a crude modular synth. I didn’t know at the time that you needed an oscillator for this system. But when I cranked it up, the resonance was awesome. So I posted it.”

It was a random comment on that post that led him to then build his own oscillator. This is the crucial recurring moment for Bamanya - the self-sustaining, erudite method to his fixation. When he wanted an effects board, or a synth, or an oscillator, his instinct wasn’t to go out and buy one. Instead, he dug into schematics, scavenged parts and built his own.

This is the true beginning and transformation of Afrorack. Using his “crappy” phone, he would post videos of his machines, how they worked and the specific sounds they produced. He would throw these DIY videos into the ether of the internet without knowing if anyone was watching. Once, he made a video with him in the actual shot, explaining the workings of an Arturia sequencer he had bought. He was then contacted by the company and given a small stipend and guidance on how to record a proper instructional video for their gear. The company then posted it on their channel, with the video quickly racking up over 400,000 views (it remains one of the most watched videos on their channel).

From there, he drifted into the orbit of Nyege Nyege, a by-now legendary record label and promotional company, whose festival and pressings are meant to incubate, launch, and promote underground music in East Africa. In 2018, after watching the Arturia video, Nyege Nyege called Bamanya and offered him a gig at a promo event of theirs. He had up to that point never performed properly. And so, Afrorack was born.

“Then, of course, COVID happens. My album was really the product of that. Nothing to do but work. I was getting all this attention as the ‘African who builds synths.’ It wasn’t a congested field.”

His 2022 debut, The Afrorack¸ is a fantastic collection of woozy minimalistic electronic pieces. The record was featured in the top 50 releases on Bandcamp that year, and received a glowing mention in Pitchfork’s spring line-up. This, added with Nyege Nyege’s cosign, finally got the ball rolling. Bamanya started getting gigs in earnest.

Since then, Afrorack has been touring the world, taking his creations across Africa, Europe, and now the West, playing his brand of infectiously strange patterns to steadily growing, always transfixed crowds. But even then, his adventurous desire for making something different, something with an avant-garde flourish emerges. Unlike most electronic musicians, he does not like executing pre-recorded recursions, preferring to leave room for some spontaneous extemporizing:

“People don’t care if you’re playing live or playing synths. They just come to have a good time. Improvising can be risky then. And so, 30% of what I do is prepared. The other 70% is improvised.”

Because of this, Afrorack’s shows have a much more organic, less predetermined feel than most electronic shows. He listens, weaves and adjusts both to the audience’s reactions and his own aesthetic choices of the moment, creating a communion with the space he occupies. It’s an intoxicating, profound experience, much more so than one would expect out of music that, all experimental affectations aside, is usually meant to just make you dance.

His curiosity and creative touch are still strong standing. At the show I attend, in addition to his regular set-up, he adds a handmade percussive instrument to the fold. It looks like an automated line of piano hammers, with bottle caps attached to the ends that create sequences of mini-snare sounds as they descend.

“I’m always building something. For me, the fact that I can perform is understanding the limitation of my performance. I only have two hands. It’s an iterative process, I guess. I refine my instruments, add foot pedals for looping. Plus, my stuff always breaks, I was supergluing the instruments before the show. So yes, I’m always building.”

The question for any artist that’s on an ascending path is always what to do next, how to grow, how to keep the momentum going. To Afrorack, the future is something that isn’t a contained, self-serving process.

“The work I’m doing is important to where I come from. I want to create something like a center where people can come and learn about electronics. A space for DJ’s to learn how to deejay, for music instruction, for people to have access to tools, instruments, 3-D printers. People can come and learn how to use all of this. This is my plan.”