by Will Floyd (@Wilf_Lloyd)

Otoboke Beaver make music that should, in theory, get stuck in your head very easily. The incendiary Japanese punk quartet do not bide their time racing to a refrain or chorus, and when they get there they tend to sing it loud, over and over, and all at once. Many of their songs revolve around a single lyric sung at differing speeds, intonations, and volumes. What can make the music difficult to commit to memory is the fact that for as determined as they are to discover some infectious new chant or groove, they appear just as determined to move on to the next one.

It is this paradoxical reliance on both repetition and constant flux where the band resides most comfortably. When it all comes together for Otoboke Beaver, the band is embodying a comedian’s commitment to reversal of expectation. It’s no wonder that they’ve taken their cues from Manzai’s comedy stylings, which also depend on rapid-fire joke exchanges, typically between two comedians. As an American their music brings to mind the sketch comedy of Tim Robinson’s I Think You Should Leave, where absurd choice is stacked upon absurd choice until your logic is overridden and the whole thing makes an inexplicable sort of sense.

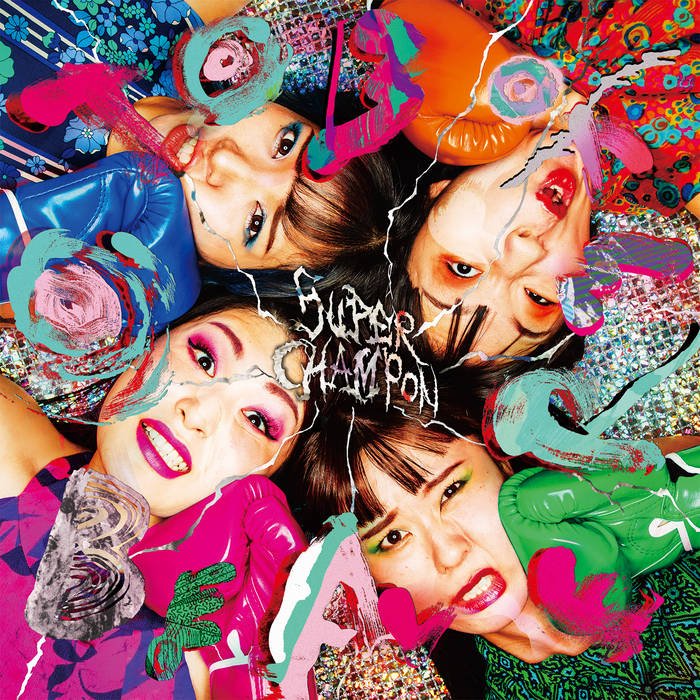

By all accounts the band have only become more unbound and free-wheeling since 2019’s ITEKOMA HITS, an album that sounds like a pop masterclass compared to much of Super Champon. The melodic guitar licks have been largely replaced by wiley noise passages, and track lengths have somehow been curtailed even further; most songs here are a full minute shorter than the majority of the songs on their debut, which averaged about two minutes. For concert-goers with early bedtimes, I have to imagine their live set is a dream.

As other reviewers have noted the predominant theme of the band’s music is a simple ‘No’—no to capitalism crippling demands, no to patriarchy, and not to common decency. Their songs might be best understood as 2-minute adult tantrums. That remains truer than ever on Super Champon: they are not maternal, they will not dish out salads, they will not be called mojo, they want to be left alone, but they don’t want to die alone. Those last two admissions—among the most vulnerable on the album—represent an ambivalence that resonates with some contemporary feminists who as of late have been trying to articulate the unique impasse of craving freedom from patriarchy and security within a traditional relationship at the same time.

When I write album reviews I always take notes on each song, but doing so for this album feels like trying to transcribe an auctioneer. By the time your mind latches onto something concrete, it’s already over. What can really be said about the handful of sub-30 seconds songs here? When the critical analyses of a song would take longer than the song actually lasts, I think I’m supposed to take the hint as a reviewer that it is not meant to be analyzed. But even for lay listeners the band’s signature restlessness might occasionally work against itself here, resulting in songs that are too transient and hurried to be internalized.

Songs like “Don’t call me mojo,” “YAKITORI,” and “PARDON?” successfully transcend this handicap by remaining evasive but still establishing distinct movements and motifs. On the matter of genre, the band has mostly rejected the punk label, saying in the past that the only aspect of it they identify with is the speed. This remains doubly true on Super Champon, through the addition of double bass pedals that somehow add ever greater velocity to their already breakneck pace.

While nothing radically new has been added to the band’s repertoire on Super Champon, they retain their position in an elite group of acts who can afford to risk repeating themselves thanks to their sheer originality. They’re also part of another burgeoning elite group of musician-humorists, whose lyrics and musical motifs derive much of their catchiness from expert comedic timing. Artists like Florence Shaw of Dry Cleaning and Charlotte Adigery have delivered some of the most memorable one-liners of the 2020s already by exploring the common ground of music and comedy. To recall an entire Otoboke Beaver song would most likely require intense memorization—the things that will get stuck in your head most seamlessly are essentially jokes, and that all depends in large part on the ear of the beholder. We’re all taking random splices of speech that our brain automatically rendered as comedy, to our graves—a throwaway line of movie or TV dialogue, things overheard in public, that thing your friend said to you in fourth grade where the inflection was just off enough to be permanently singed into memory. These are the kinds of moments that Otoboke Beaver create with seeming ease. Whatever uncanny delivery or wacko time signature shift your mind latches on to here may just live rent-free in your brain forever.