by Mike LeSuer (@zebraabraham)

It’s the year 2017 and it’s become frustratingly evident that much of the information America consumes is based on emotional impact rather than bipartisan fact. Law and order in the age of the Comments Section has followed its natural course of development, and, as any thinkpiece reiterating the necessity of Kendrick Lamar is certain to tell you, the art/life dialectic remains well-balanced. It’s no wonder certain veterans of underground hip-hop have suddenly emerged as prominent voices in the genre’s mainstream discussion, given their proclivity to spin poignant tales of social injustice, mental (or physical) illness, and substance abuse to an audience of empathetic listeners looking to have their own experiences soundtracked by an angsty beatsmith.

Re-enter Billy Woods - a staple of NYC’s subterranean hip-hop community with a heidey-ho-neighbor commitment to facial obscurity - whose Today, I Wrote Nothing disrupted this blossoming socially-conscious era of rap in 2015 with an abstract noisescape more reminiscent of El-P’s alt-rock era than Producto’s highly-successful Run The Jewels project. Opposing the direct action and brutal irony of his recently-surfaced underground peers, its Woods’ MO to grace his listeners with hard-hitting truths in the form of dense, culture-wary poetry which reminds us that Kurt Vonnegut and Jerry Springer not only exist in the same universe, but are also equally responsible for influencing the present condition of our country’s collective consciousness.

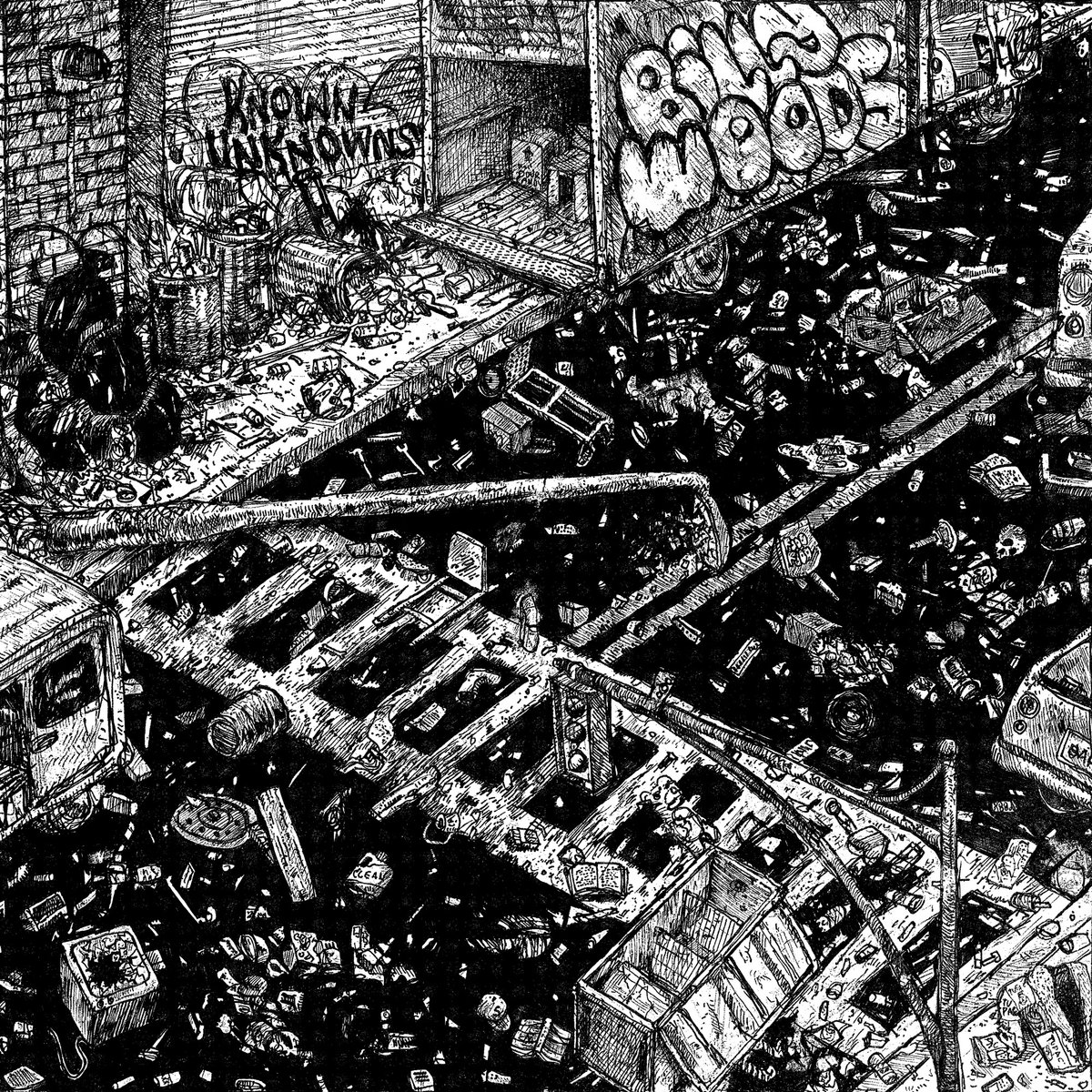

Yet as his message continues to align with that of conscious hip-hop’s popular discourse, his delivery of ideas further distances him from the zeitgeist: if you were to strip Billy’s discography of instrumentation and chart the emotional palette of his isolated vocals on an EKG monitor, you’d be looking at a flatline spanning about six hours. In other words, Woods’ delivery is an endless barrage of gruffly enunciated spoken word indifferent to the variety of production providing little emotional influence to his verses. Perhaps this has been made most apparent in his progression from the avant garde beats contributed by his Backwoodz labelmates on Today to Blockhead’s playful sampling on Woods’ new release, Known Unknowns, which frequently veers a near 180 from the combative instrumentation of its predecessor.

The first taste of Unknowns arrived in the form of the twee-indebted “Groundhogs Day,” and was followed shortly thereafter by a collaboration with serial jokesters Aesop Rock and Homeboy Sandman. Though this pair of singles may be somewhat misleading as a representative preview of the album, they communicate a theme of extroversion mostly unfamiliar to Woods’ music since 2013’s Dour Candy, which shines through in the linguistic potpourri of “Wonderful,” the playful scratching of Aes and Blockhead’s production throughout, and the forgivably unconvincing Cobain intonations supplied by vocalist Barrie McLain to close the record. While Billy’s flow remains unflappable, the community of artists surrounding him configure a considerably less claustrophobic experience than his recent work (mostly in conjunction with co-conspirator Elucid), inspiring the rapper to tell the same stories in a significantly different context.

Meanwhile, highlights like “Police Came To My Show” and “Washington Redskins” prove pure Woods: the former pins a subject of social contention against the emcee’s wry self-deprecating sense of humor (“zero merch sales later I’m at the bar”), while the latter offers a brief narrative dissertation on racial inequality in response to the Gil Scott-Heron soundbite that punctuates the previous track. As typical of Woods’ work, much of the message embedded in Known Unknowns surfaces via samples - despite the relatively passive lyrical content of “Police Came To My Show,” the brief “Sound of da Police” extract in the closing minute seems to represent the submerged portion of the artistic iceberg.

Though Woods continues to appease Rap Genius scholars with his juggling of mismatched cliches, decontextualized audio samples, and left-field pop culture references, Known Unknowns proves another 60 minutes of mono-enunciated Woodspeak meticulously crafted and entirely pertinent to more complex conversations on being a minority in America. As the penultimate “Keloid” recapitulates, every zenith of assonance (describing a racist as a “Ted Koppel doppelganger,” notably) is comfortably housed within an apt meta commentary on hip-hop, examining white phobias of the genre as synecdochical racial body horror (“trigger warning before every verse / can’t feel it if it doesn’t hurt”). The fact that such significant lines are delivered with the same articulation as “Groundhogs Day”’s generic chorus of “I wake up and smoke weed” forces the listener to examine every word and diagnose for themselves the emotions and context behind the author’s unique literary voice.