by Benji Heywood (@benjiheywood)

Chernobyl and Three Mile Island – both famous sites of unprecedented manmade disaster, and both recipients of slick TV productions, one great, and one… not so great. For a band like Chat Pile, whose sludgy noise-core is deeply indebted to the monsters of the silver screen, they must be wondering what Picher, Oklahoma has to do to get a movie deal. Picher – the nation’s biggest manmade disaster you’ve never heard of – is the Oklahoma town so polluted from nearly a century of lead-zinc mining, the US government in 2008 paid everyone to get the fuck out of dodge. Picher is now a ghost town, the air toxic from the numerous chat piles that tower above it like lethal Alps, the ground so destabilized from mining that at any moment it could collapse beneath your feet.

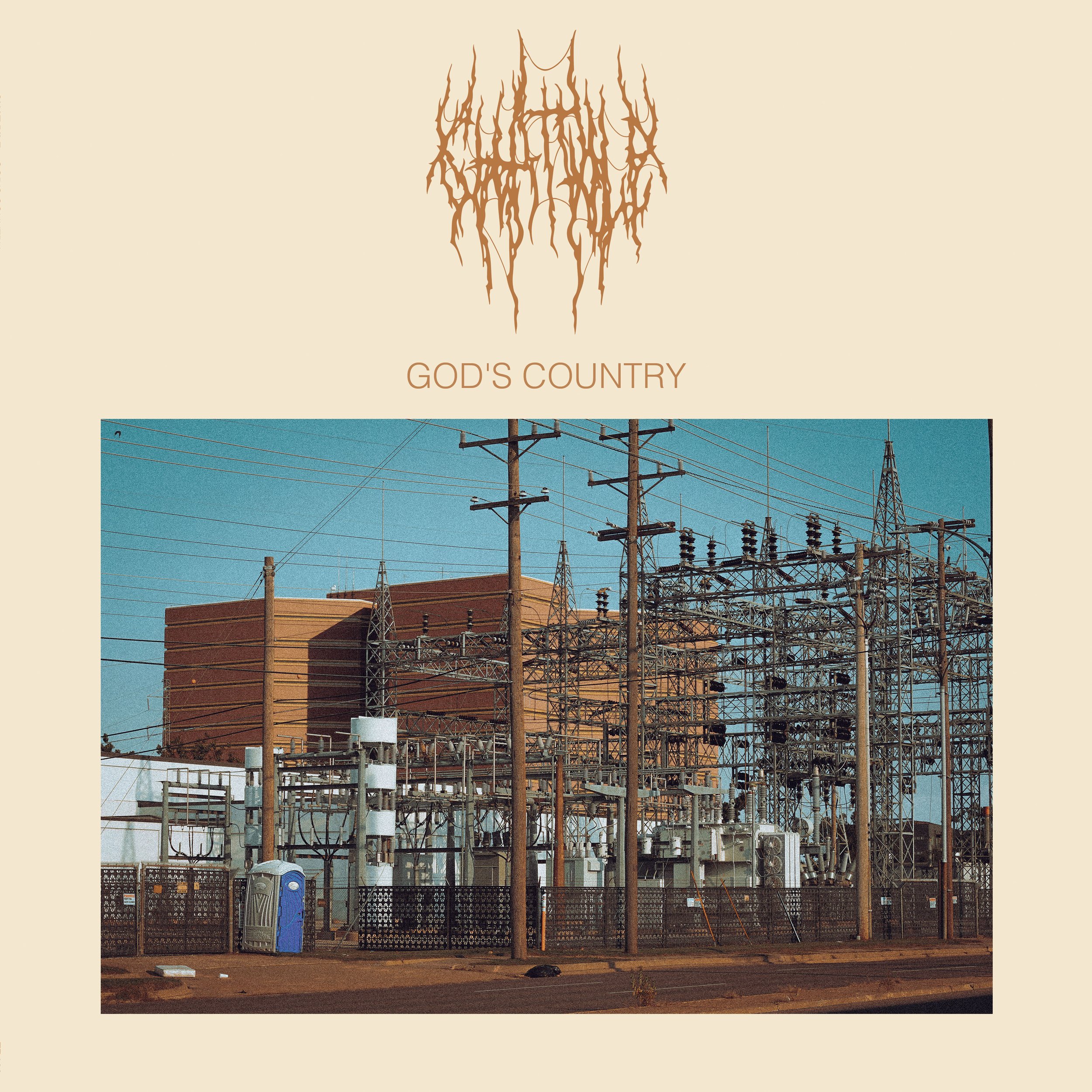

The setting of an abandoned toxic waste site is an apt one for Oklahoma’s Chat Pile. Listening to their highly anticipated debut album God’s Country is like inhaling lead dust while running from a killer chasing you with a bloodied pickax. “There’s more screaming than you’d think,” howls vocalist Raygun Busch on the album’s unsettling opener “Slaughterhouse.” The lyric might as well describe the experience of listening to God’s Country itself. It’s a masterpiece of sludge, noise, terror, and industrial hardcore.

Standing on the shoulders of heavy music titans Eyehategod, Korn, and Ministry, Chat Pile have made an album that’s as terrifying to listen to as it is deeply lyrically unsettling. To call the bowel-loosening low end of God’s Country the century’s sludgiest is not hyperbole; Chat Pile deploy a lethal arsenal of detuned sonic bombardment that is nauseating, beautiful, and punishing, an ideal foil for the ravings of Raygun Busch, whose yelps, howls, and blood-curdling screams are relentlessly unhinged.

“Slaughterhouse” begins with drummer Cap’n Ron’s jerking stop motion drum part. The kick and snare tones are wickedly discombobulating – at once natural and digital – a differentiating signature that earns Chat Pile the Big Black comparison and is accomplished by the Cap’n recording his drum parts with an eKit sans click track. It’s a cool approach that allows Chat Pile to appear inhumanely industrial while remaining imperfectly human. “Slaughterhouse” kicks in with one of the best intro lines of a song about industrialized killing – “hammers and grease!” – before bassist Stin and guitarist Luther Manhole unleash the first of the album’s plethora of body-pummeling riffs.

A track one like “Slaughterhouse” would be hard to top but “Why” does just that. Chat Pile’s devastatingly heavy critique of what the band calls the “sick irony to how a country that extols rhetoric of individual freedom, in the same gasp, has no problem commodifying human life as if it were meat to feed the insatiable hunger of capitalism” is both rhetorically and musically effective. Over a Helmet-on-cough-syrup riff, Raygun sounds almost childlike in his questioning: “Why do people have to live outside?” As his frustration builds, keeping pace with the music’s intensity, you easily begin to wonder the same thing. What the fuck are we doing?

“Why” is brutal sounding, but the song’s effectiveness is due to Raygun’s vulnerability, which acts as an emotional throughline for much of God’s Country. When he admits he “couldn’t survive on the streets,” when he asks if you’ve ever had “ringworm” or “scabies” – you feel as brutalized as he. On “I Don’t Care If I Burn,” Raygun admits to “thinking about killing you every day” in such a frank, yet broken tone, you fucking believe him. Over a field recording of something scraping and the pops of a cooking fire, you can almost smell the flesh burning as Raygun sings dead-panned “Cause, you may not see me now/But, motherfucker/I see you” before unleashing a brief, brittle scream, one worthy of all the jump-scares in Hollywood horror films.

As a resident of Los Angeles, it’s easy to relate to what Chat Pile call the “real American horror story,” to join Raygun and co. in the muck and mire of a bleak, desperate world. The album’s nine tracks depict some of the most traumatic scenes life offers, and yet, one can’t help but wonder if there’s a bit of fun to be had. Catharsis is real, and if you enjoy being scared in the movies, then why can’t you enjoy when a person screams “I wanna wear your flesh/When I look through my eyes/I wanna be/You/I’m a monster too” – like the protagonist in the album’s final, menacing track “grimace_smoking_weed.jpeg”? There’s a long pantheon of shock in which God’s Country belongs. With its bone-rattling sound and Raygun’s horror-core lyrics, this album is just begging to be the latest thing Christian conservatives can hide their children from.

Throughout God’s Country it’s hard to tell if what we’re hearing is fictional or real life. Should we take the lyrics we find in “Anytime” seriously – “At first your hand was in mine/There, smiling and walking/Then the world split open/Think there was brain on my shoes” – or are we being offered a glimpse into a nightmarish fantasy world, where no-limit torture porn is the soup de jour? Elsewhere on “Wicked Puppet Dance,” Raygun offers this insight: “She says vein stuff freaks her out so I keep quiet/Everyone says they can’t handle vein stuff til they try it.” Knowing the Bible Belt’s struggle with methamphetamine use makes this line unnervingly powerful. It evokes the kind of lived-through experience more commonly found in memoirs than in metal music.

This a-similitude seems to be the point. For all its spectacular violence, the music of Chat Pile is symbolic of what is truly horrifying: the unceasing tsunami of American grief played out in rising rates of suicide, overdose, mass shootings, and homelessness. As we live through the effects of climate collapse and plunder monkey capitalism, it’s not hard to see Chat Pile’s grotesque account of modern life (fictionalized as it may be) as a depiction of us getting what we deserve. It’s like the part in the slasher film when a character does something stupid – don’t go back in the house, you idiot – and gets disemboweled for it. There is some satisfaction there, even if it’s the type of schadenfreude that helps alleviate our own death anxiety. In the same way, God’s Country is a musical tome of our discontent. It would be enjoyable if it were a film, but sadly, our American horror story is heartbreakingly real.